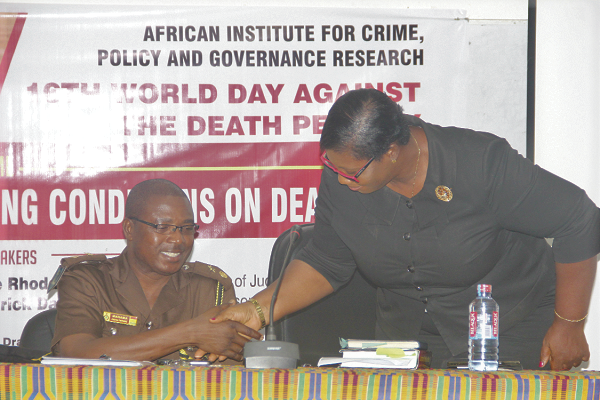

Commercial vehicle drivers (‘trotro’ drivers) who experience police corruption are more likely to break traffic laws. That’s the finding from a new study by three members of Africa Institute for Crime, Policy and Governance Research: Dr Tankebe, Dr Boakye, and Mr Amagnya.

The study also found that the drivers were more inclined to assist the police maintain law on the roads if they are treated fairly by the police. The study, published in the international peer-reviewed journal Policing and Society, was based on survey data from 415 drivers in Accra and Kumasi.

“Our findings show that police can reduce traffic violations by curbing corruption among traffic officers. They may be able to increase the flow of information from commercial vehicle drivers by improving the fairness of their interactions with these drivers”, the authors concluded.

Find full study here